In my previous article, A Survival Compass: How to Navigate the 21st-century Risk Landscape, I argued that base rates are our most powerful tool for navigating the complex world of risk. Our ancestral instincts, honed over millennia of evolution, often fail us in the face of modern, abstract threats. Base rates offer a much-needed anchor for our risk judgments and decisions.

To use this tool effectively, we must first understand how statistics fit into our natural risk judgment and decision-making (RJDM) processes. In this article, we'll explore:

Our discomfort with uncertainty (the unfamiliar).

The cognitive triad that enables us to shape beliefs (and evaluate risks).

The challenges preventing us from using base rates effectively and when/why these rates might be useless.

But first, a quick recap of key points from our previous discussion:

Base rates provide a statistical foundation for our risk assessments.

They help counter the influence of emotions and biases on our decisions.

Effectively leveraging base rates can significantly improve our risk judgments and choices.

Incorporating base rates into our RJDM processes takes practice and skill, just like learning to use a map and compass. By mastering this competency, we can navigate life's uncertainties with greater confidence and precision.

Certainty-Seeking in an Uncertain World

As human beings, we have a deep-seated need to reduce uncertainty, especially when it comes to threats, hazards, and risks. We crave a sense of control and predictability, even in the face of complex or ambiguous situations.

For example, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a stark reminder of our discomfort with uncertainty. The rapid spread of the virus, the lack of clear information about its origins and effects, and the unpredictability of its impact on our lives have led to widespread feelings of anxiety and unease.

Cultivating high safe-esteem involves recognizing that there is often little, if any, correlation between how confident we feel about our risk judgments and their accuracy.

To cope with this uncertainty, we often resort to various cognitive strategies and heuristics that give us a sense of understanding and control, even if that sense is illusory. One such strategy is the use of rating scales and categorizations.

We have a remarkable ability to rate and rank just about anything, even in the absence of clear criteria or data. These ratings give us a sense of order and predictability, making the world feel more manageable.

Think about how often we use rating scales in our daily lives, from restaurant reviews to movie ratings to risk assessments. These simplified metrics help us navigate complex decisions quickly and with a sense of confidence. A five-star rating or a color-coded risk level can give us a quick, intuitive sense of quality or safety, even if the underlying criteria are unclear or inconsistent.

Today, we understand that our drive for certainty can lead us to prioritize the feeling of "resolution" over accuracy when making risk judgments and other types of assessments. A doctor who has seen several recent cases of a rare disease may overestimate the likelihood of that disease in future patients, even if the overall base rate remains low. The vividness of recent cases can create an illusion of validity that overrides the statistical reality.

As for the base rate fallacy, this phenomenon is so pervasive that it has earned its own name in the catalog of cognitive biases: the Illusion of Validity. Cultivating high safe-esteem involves recognizing that there is often little, if any, correlation between how confident we feel about our risk judgments and their accuracy.

The Cognitive Triad: Feelings, Memories, and Base Rates

When we face life's uncertainties, our judgments are shaped by a triad of cognitive influences: feelings, memories, and (pseudo) base rates. These elements intertwine within our minds, crafting a tapestry of decision-making processes that guide our risk perception.

FEELINGS, often a gut reaction to a situation, can sway our decisions with a potent mix of emotional responses. Research on Cultural Cognition, pioneered by Dan Kahan, has shown that our emotions can shape our judgments regardless of our education, intelligence, or numeracy, especially when dealing with identity-forming and value-laden concepts like risk. Kahan's work demonstrates that people tend to conform their perceptions of risk to their cultural worldviews, which are deeply tied to their sense of identity and social affiliations.

This means that even highly educated and numerate individuals may dismiss or reinterpret statistical evidence that contradicts their emotionally-held beliefs about issues such as climate change, gun control, or vaccination. Our feelings, therefore, can be a powerful force in shaping our risk judgments, sometimes leading us to prioritize consistency with our cultural identity over objective accuracy.

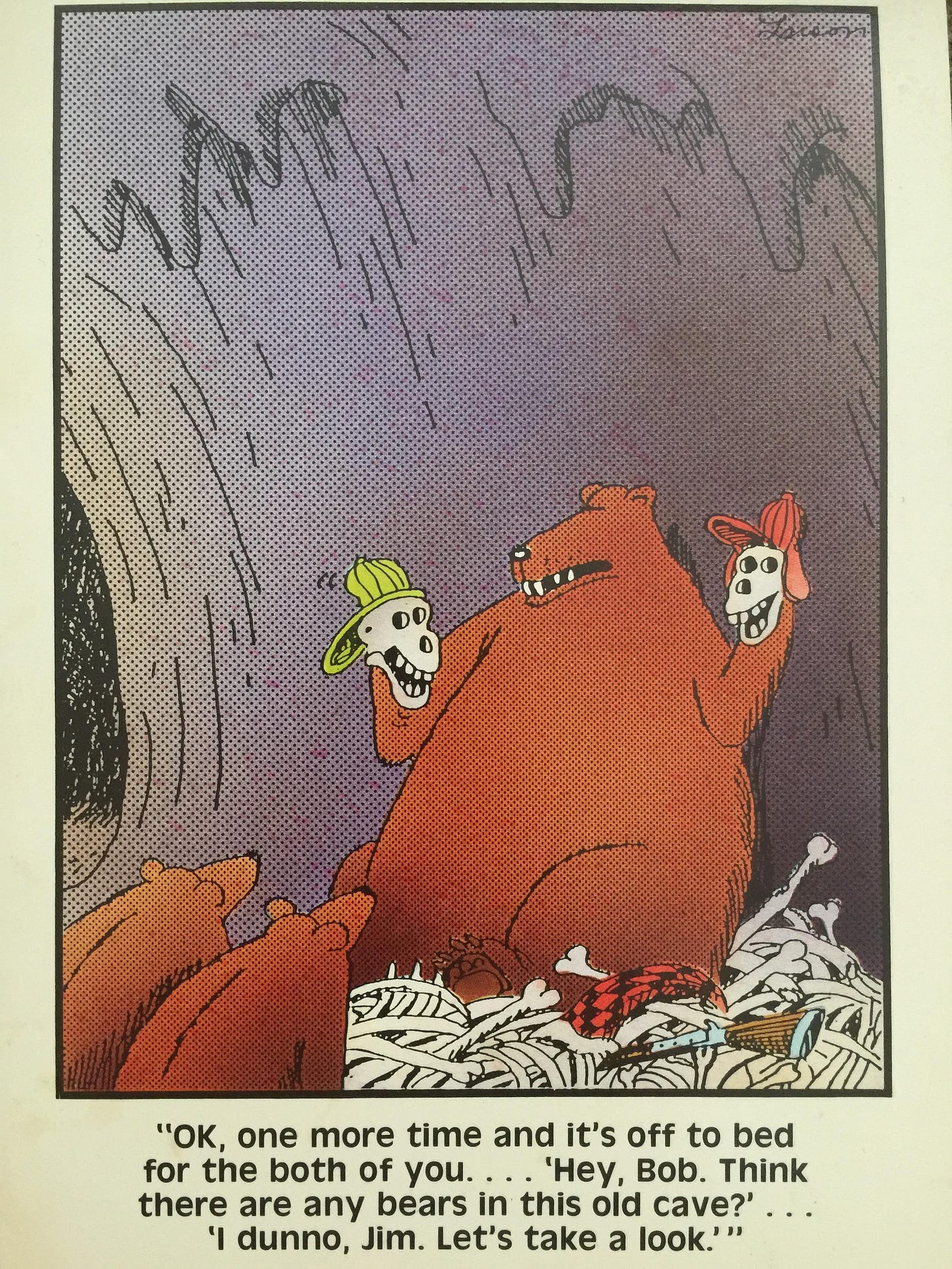

MEMORIES, the archives of our past experiences, offer a reference point, coloring our expectations of future events. However, the saliency or source of these memories can often warp their weight in our risk perception and judgment. For example, vivid personal experiences or emotionally charged anecdotes tend to be more easily recalled and can disproportionately influence our assessment of risk, even when they are not representative of the broader statistical reality. This is known as the availability heuristic, a mental shortcut that leads us to overestimate the likelihood of events that are readily available in our memory.

Moreover, the source of our memories and information can also bias our risk judgments. We are more likely to trust and rely on information that comes from sources we perceive as credible or that align with our pre-existing beliefs, even if that information is not statistically accurate. This confirmation bias can lead us to seek out and prioritize memories and information that support our existing views on risk, while discounting or ignoring evidence that contradicts them.

As a result, our memories can serve as a double-edged sword in the realm of risk judgment, providing valuable experiential knowledge but also potentially skewing our perceptions.

BASE RATES (ideally) provide a statistical backbone for our risk judgments, grounding them in the objective frequency of events. For most of our evolution as a species, and in many instances, to this day, the only base rates we had were the memories of our direct or proximate experiences.

The emergence of language allowed us to acquire social knowledge, mostly in the form of stories and anecdotes. These narratives served as a way to share and aggregate risk-related information across individuals and generations, expanding our collective understanding of threats and hazards.

While these early forms of base rates were the best available option for much of our history, they were often limited in their predictive validity. The development of more systematic data collection and analysis techniques has allowed us to create more robust, statistically sound base rates. (And, as I argued earlier, double our lifespan and vastly increase our survival chances in just the last 100 years.)

Despite these advancements, we often still struggle to effectively incorporate statistics into our risk judgments, defaulting to more intuitive or accessible forms of information. Recognizing this tendency and actively working to integrate actuarial base rates is a key challenge in improving our risk decision-making. This base rate neglect or fallacy holds its prime stature among the most cited and studied cognitive biases, and you can read more about it here:

Together, these elements—feelings, memories, and base rates—form a complex cognitive process where feelings might override statistical realities, memories can bias our expectations of future occurrences, and relevant statistics are neglected in favor of more emotionally salient information.

Beyond Cognitive Bias: Effective Base Rate Utilization

While cognitive biases like base rate neglect and the illusion of validity offer a partial explanation for our struggle to use statistical information effectively, they are just the tip of the iceberg. Many other challenges, often more severe and systemic, hinder our ability to properly utilize base rates and statistical data in real-world and everyday risk judgment and decision-making. These range from data availability and quality to communication efficacy and domain knowledge.

Simply being aware of cognitive biases and heuristics is a good starting point, but it's not enough to guarantee proficient interpretation and application of base rates. To truly harness the power of statistical information, we must dive deeper into the practical, methodological, and contextual factors that shape our risk assessment processes.

To truly harness their power, we must ask key questions:

Which base rates are the most valuable (aka, predictive) for risk judgment and decision-making (RJDM) in our specific case?

When should new or real-time information update or replace base rates?

And, under what conditions do simple heuristics and decision-support frameworks outperform base rates?

It's important to note that not all base rates are created equal. As base rates become more sophisticated, moving from personal experiences to clinical observations and finally to statistical/actuarial data, their predictive power generally increases.

Our long-term goal is to address these questions and elevate your risk 'navigational' skills, with or without base rates. But first, let's explore some of the top challenges beyond cognitive biases:

IGNORANCE

A fundamental challenge in using base rates is the lack of relevant data. Too often, the information we need for informed risk assessments is unavailable, too costly to obtain, or simply ignored.

Consider planning a road trip from New York to Chicago. Ideally, you'd compare motor vehicle accident rates for potential routes. But this data might be hard to find or interpret, leaving you to rely on less accurate risk proxies, like personal anecdotes or media reports.

Similarly, when traveling to a new city, reviewing its specific crime rates would be prudent. However, this information may be inaccessible or unreliable, forcing us to make judgments based on incomplete or potentially misleading data.

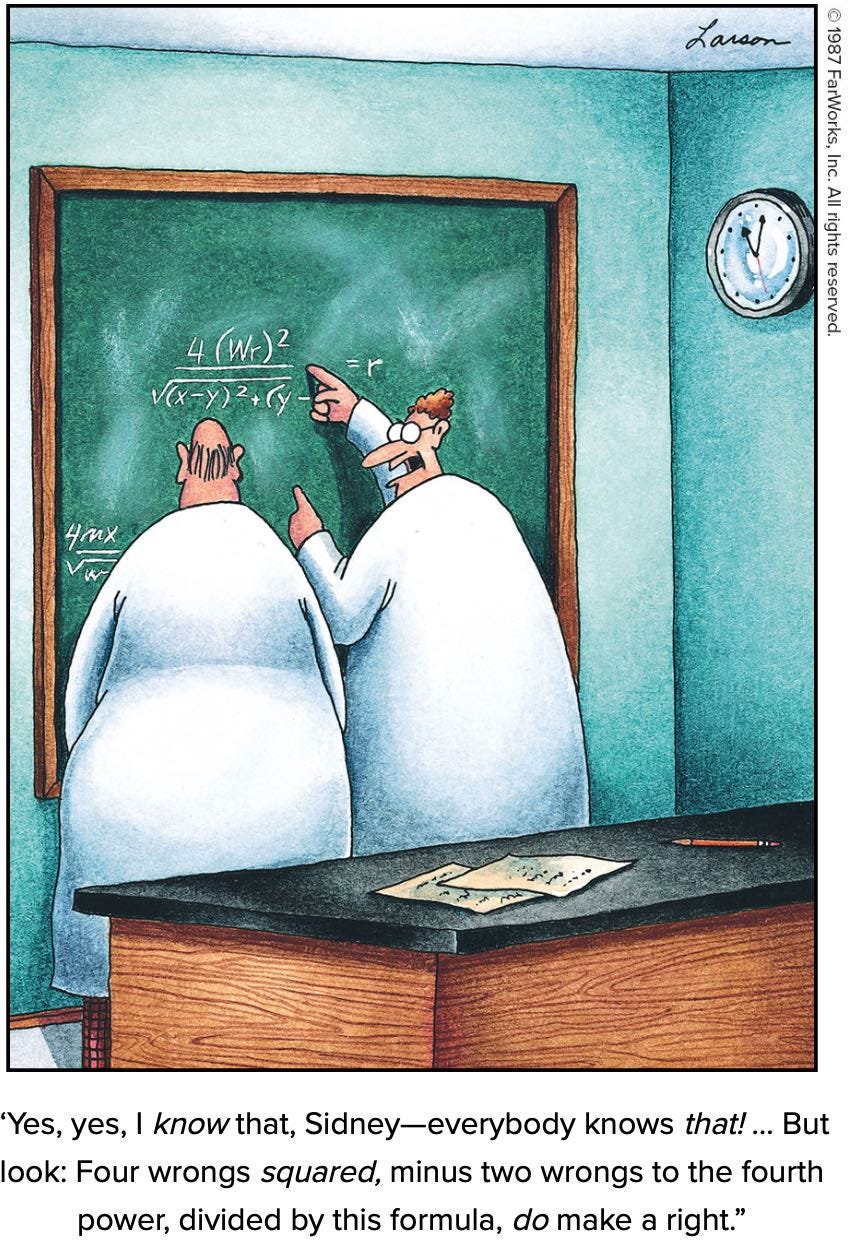

INNUMERACY

Even when relevant data is available, innumeracy – the inability to understand and work with numbers, especially statistics – can hinder our ability to use it effectively. Many people, even risk-centric professionals, struggle with basic probabilistic thinking.

A common manifestation is confusing qualitative risk ratings with actual rates or ratios. For instance, a five-point risk scale (low to high) is often misinterpreted as a quantitative measure. In reality, these ordinal scales can't be used for arithmetic operations, leading to flawed comparisons and decisions.

A classic example of innumeracy in a high-stakes context is the Harvard Medical School study by Casscells, Schoenberger, and Grayboys (1978). The researchers asked a group of medical students and staff to estimate the probability of a patient having a disease, given a positive test result, the disease's prevalence, and the test's false positive rate. Nearly half of the respondents significantly overestimated the probability, failing to properly account for the low base rate of the disease in the population. Even highly educated individuals can struggle with basic probabilistic reasoning, leading to misinterpretations of critical risk data.

AMBIGUITY

The inherent ambiguity of risk as a concept can also hinder effective base rate usage. "Risk" is often used vaguely, and qualitative descriptors like "low," "medium," or "high" have little consistent meaning.

Moreover, risk ratings often aggregate multiple, distinct metrics under broad categories like "personal risk" or "crime risk." Without breaking these down into specific, measurable components, the predictive value of the associated base rates can be compromised.

A travel advisory might classify a country as "high risk" due to a mix of factors like petty theft, violent crime, and political instability. But without disentangling these components and their respective base rates, it's challenging for travelers to make nuanced safety decisions.

Disambiguating risk categories – separating violent crimes from property crimes, or injury accidents from health hazards – allows for more precise risk assessment and effective base rate application.

IRRELEVANCE

For base rates to be useful, they must be directly relevant to the specific risk being assessed, at the appropriate level of granularity. Overly broad or aggregated data can be misleading and potentially dangerous.

Imagine you're considering moving to a new city abroad. country-wide crime statistics might paint a general picture, but they will most likely mask important variations between cities. Basing your decision on this broad data could lead you to overlook critical risk differences.

This "flaw of averages" applies to geographic, temporal, and demographic aspects of risk. Base rates must be tailored to the relevant location, time period, and population to support effective judgment. Failing to account for these specifics can render base rates irrelevant and hinder sound decision-making.

The "reference class problem," as statisticians call it, applies to geographic, temporal, and demographic dimensions of risk. Your risk profile as a 25-year-old tourist in Mexico City's Roma Norte neighborhood on a Tuesday afternoon is vastly different from that of a local business owner in Iztapalapa at midnight. Base rates must be tailored to these specifics to support effective judgment. When we fail to match our base rates to the right reference class, we might as well be making decisions based on random numbers.

What’s Next?

As we've seen, leveraging base rates effectively in risk judgment and decision-making is a critical skill that is often hindered by challenges like ignorance, innumeracy, ambiguity, and more. Overcoming these obstacles is the first step towards developing a higher safe-esteem – the ability to make informed, accurate risk assessments and decisions.

But this is just the beginning of our journey. In upcoming posts, we'll dive deeper into each of these challenges, exploring practical strategies to conquer them and sharpen our base rate skills. We'll also examine the psychological and cognitive factors that shape our risk perceptions and discover how emerging technologies, from big data analytics to artificial intelligence, can enhance our risk navigation abilities.

We might explore how a new AI-powered tool could help travelers assess destination-specific risks by aggregating and analyzing multiple data sources, from local crime rates to health hazards, providing personalized, real-time risk assessments.

By continuing this exploration together, we'll uncover new insights and strategies for making better decisions in the face of uncertainty. Whether you're a business leader navigating complex operational risks, a healthcare professional making high-stakes treatment decisions, or an individual seeking to enhance your personal safety, developing your safe-esteem is a journey worth taking.

In case you missed them, these earlier posts provide the background and build-up to the above points:

Beyond Instinct

Our world is growing more complex and uncertain by the day. Institutions we once trusted are now doubted. Disinformation and conspiracy theories bombard us from all sides. Our environment is vastly different from the one in which we evolved as hunter-gatherers, yet the fundamental human need to survive and thrive remains unchanged. To meet this need in …

A Survival Compass

Survival as Predictive Excellence Our very survival, both as individuals and as a species, hinges profoundly on the quality of our risk judgment and decision-making, barring those threats and hazards beyond human control. The task of prediction - our ability to evaluate what is likely to cause us harm or prove fatal - has undergone a gradual evolution, …